Don't Just Do Something, Stand There

- By Jon Hagen

- •

- 01 Feb, 2021

Contemplating Complexity Should Lead to Humility

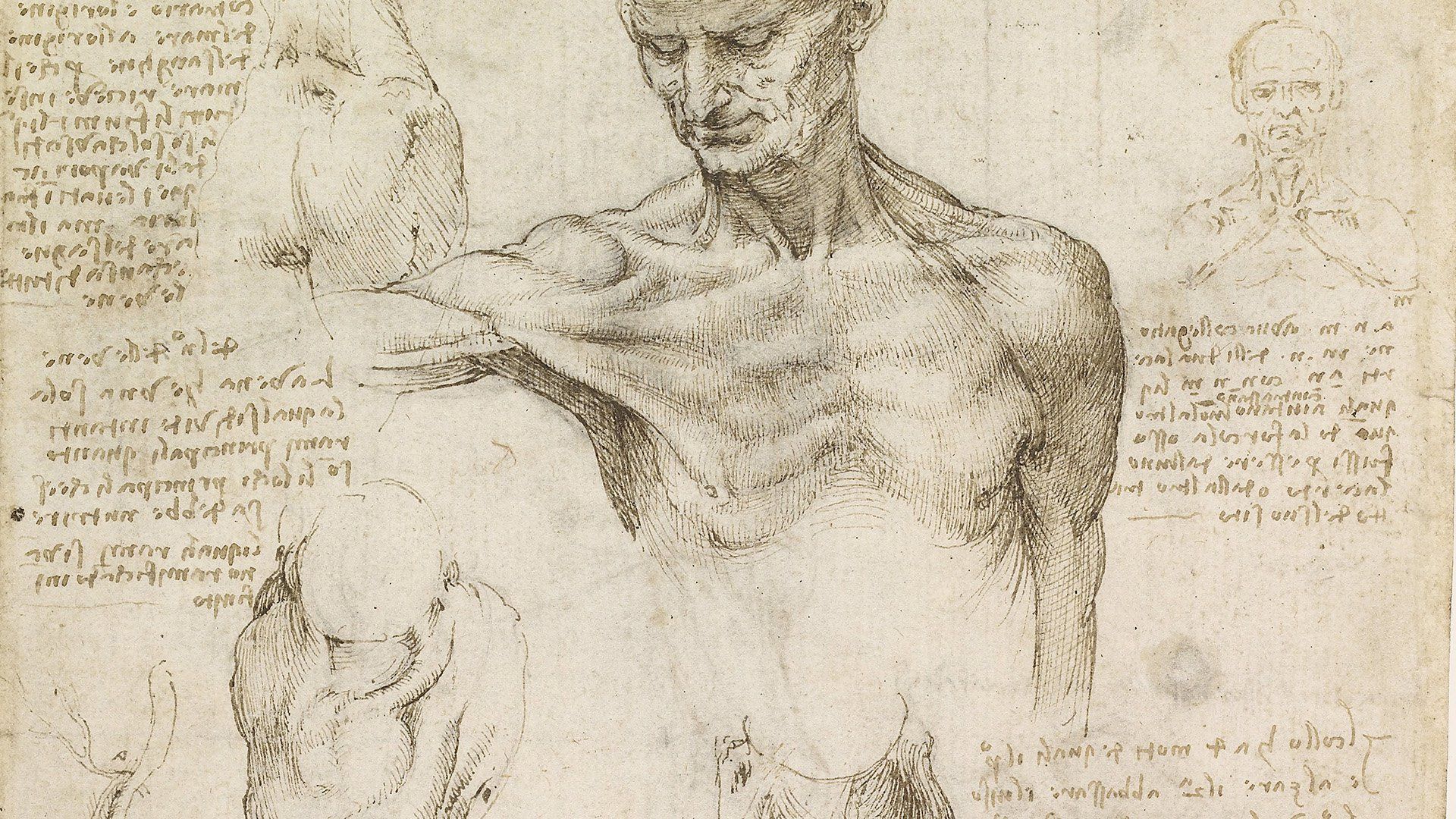

I was a teenager on a tour of my Dad’s alma mater when we ended up in a lab room full of dead bodies. Cadavers, to be exact. Skinless human bodies, each on its own table, for students to examine. I remember standing there, trying to take in what laid before me. In my mind, in that moment, I wasn’t seeing dead people as much as I was seeing intricate works of art—absolutely fascinating musculature with its woven threads and fibers wrapped around an inner architecture of static bone.

Many years later, when my older son was in college, he and I would look at medical renderings in his anatomy textbooks. One picture in particular has stayed with me—a cutaway drawing of a head without skin revealing how the twelve cranial nerves project upward from the spinal cord and innervate the bones and muscles of the human face. I was thrown back to that room full of cadavers. The amount of detail and information was overwhelming. I was momentarily stopped. The design, each nerve with its own purpose, and the whole put together, was awe-inspiring. To this day, I have a million questions about all of that.

It takes time, and a lot of it, to appreciate, let alone value and attempt to understand, the beauty of complexity. But apparently we don’t have that kind of time—either personally or culturally. Recently published books such as The Death of Expertise by Tom Nichols, and The Madness of Crowds by Douglas Murray, attempt to capture our cultural moment in time. My current favorite (I confess, I’ve not finished it) is Leadership and Self-Deception by The Arbinger Institute.

It also takes time and grace to understand the challenges of relational complexity. Not a day in my office goes by where you won’t find me encouraging couples to slow down in their communication with one another. The zero-gap between stimulus and response creates all kinds of collateral trouble. Think knee-jerk reaction. Think reactionary social posts. No sooner does she finish a sentence then he jumps her with his own two cents. Yes, he likely has some truth to the point he’s trying to make, but there’s no way he possesses ALL the truth on his side. If neither party is willing to acknowledge this reality—that both sides have some truth within them—then they’re doomed to a death spiral at both the personal and national level.

One

dynamic that contributes to relational complexity is inattentional blindness. Daniel

Simons is an experimental psychologist who’s famous for his demonstration that

people who are asked to focus on counting basketball passes amongst a group of

people can completely miss seeing a gorilla actor walking right through the middle

of the group. Our eyes and brains are limited to how much information we can

take in at any given moment. The more complicated a situation becomes, the more

likely we are to miss important information. To test yourself on this concept, watch

this 5-minute video and see how you do:

Since there’s so much going on in any one person’s life, I suspect that little in our world escapes inattentional blindness. That even includes how we read the Bible. Since I’ve had more clients over the past year showing up with signs of trauma, I’m reading more material on the subject and trying to understand what trauma does to a person. It’s complicated, to say the least. This may seem obvious on the surface, but more than one writer on trauma indicates that experiences of trauma will be a significant factor for one’s reading strategy in working through the Christian Scriptures. One author puts it this way:

“We see only what we are prepared or taught to see. When we read the Bible, we focus on our own topic of interest, on what we are looking for, such as the status of women, or the theological message, or what we can learn about history. In doing so, we become blind to everything else.” That’s selective attention, precisely.

All of this to say that what I’m after here is the hope that some of us will slow down, be still, even, long enough to let the complexity of our life, our day, our world, humble us. Intellectual humility (if I can separate this from moral humility) recognizes there is far more going on in any given circumstance or relationship than we can take in and assimilate; therefore, our attitude and responses toward others with whom we disagree should be tempered. “Let every person be quick to hear, slow to speak, slow to anger” (James 1:19).

If only spouses would learn this. If only parents and their children could experience this. If only neighbors shared this. If only churches modeled this. If only . . .

Because God resists the proud but gives grace to the humble.